Photogallery

For our starter kit, we will be making a photogallery website that uses a server to store images. We’ll outline the design process and go over our front and backend code.

The link to the repository is found here

For our starter kit, we will be making a photogallery website that uses a server to store images. We’ll outline the design process and go over our front and backend code.

The link to the repository is found here

For our Web Development Starter Kit, we’ll be utilizing FastAPI, an essential toolkit for those creating websites and web applications. Consider FastAPI as a collection of foundational tools that developers employ to build and manage the unseen components of websites or apps. These components are crucial for functions like securely transmitting your data during sign-ups or log-ins.

While there are other frameworks like Flask, Django, and Tornado, each serving distinct purposes, FastAPI stands out for its ease of use and robust built-in features. This means you can achieve more with less coding effort, making it an excellent choice for both quick website deployment and for those new to web development, thanks to its gentle learning curve.

Complete Getting Started before doing this.

Create an app.py file at the root level of your project folder. Inside of it, copy these lines of code.

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request, HTTPException

+from fastapi.responses import HTMLResponse, JSONResponse

+from fastapi.staticfiles import StaticFiles

+from fastapi.templating import Jinja2Templates

+from pydantic import BaseModel

+import uvicorn

+

+app = FastAPI()

+

+static_files = StaticFiles(directory='public')

+views = Jinja2Templates(directory="public/views")

+

+app.mount('/public', static_files, name='public')

+app.mount("/css", StaticFiles(directory="public/css"), name="css")

+app.mount("/js", StaticFiles(directory="public/js"), name="js")

+

+class Image(BaseModel):

+ title: str

+ description: str

+ src: str

+

+images = {}

+@app.get('/', response_class=HTMLResponse)

+def get_home(request: Request) -> HTMLResponse:

+ return views.TemplateResponse("main.html", {"request": request, "images": images})

+

+

+@app.post("/images", response_class=JSONResponse)

+def post_image(img_data: Image):

+ # add data

+ img_id = len(images) + 1

+ images.update({img_id: img_data})

+ return {"img_id": img_id, **img_data.dict()}

+

+@app.put("/images/{img_id}", response_class=JSONResponse)

+def modify_image(img_id: int, img_data: Image):

+ #modify data

+ if img_id in images:

+ images.update({img_id: img_data})

+ return images[img_id]

+ raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Image not found")

+

+@app.delete('/images/{img_id}', response_class=JSONResponse)

+def delete_img(img_id: int):

+ if img_id in images:

+ return images.pop(img_id)

+ raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Image not found")

+

+if __name__ == "__main__":

+ uvicorn.run("app:app", host="127.0.0.1", port=8007, reload=True)

+

+from fastapi import FastAPI, Request, HTTPException

+from fastapi.responses import HTMLResponse, JSONResponse

+from fastapi.staticfiles import StaticFiles

+from fastapi.templating import Jinja2Templates

+import uvicorn

+You have to create these folders at the root of project, which is the folder you opened when creating the project. You can see what your root is by looking at what folder you’re in.

In this image, we’re in the Photogallery root.

app = FastAPI()

+

+static_files = StaticFiles(directory='public')

+views = Jinja2Templates(directory="public/views")

+

+app.mount('/public', static_files, name='public')

+app.mount("/css", StaticFiles(directory="public/css"), name="css")

+app.mount("/js", StaticFiles(directory="public/js"), name="js")

+class Image(BaseModel):

+ title: str

+ description: str

+ src: str

+

+images = {}

+We’re going to keep the information contained within Image in a dictionary as defined by images = {}

@app.get('/', response_class=HTMLResponse)

+def get_home(request: Request) -> HTMLResponse:

+ return views.TemplateResponse("main.html", {"request": request, "images": images})

+

+@app.post("/images", response_class=JSONResponse)

+def post_image(img_data: Image):

+ # add data

+ img_id = len(images) + 1

+ images.update({img_id: img_data})

+ return {"img_id": img_id, **img_data.dict()}

+

+@app.put("/images/{img_id}", response_class=JSONResponse)

+def modify_image(img_id: int, img_data: Image):

+ #modify data

+ if img_id in images:

+ images.update({img_id: img_data})

+ return images[img_id]

+ raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Image not found")

+

+@app.delete('/images/{img_id}', response_class=JSONResponse)

+def delete_img(img_id: int):

+ if img_id in images:

+ return images.pop(img_id)

+ raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Image not found")

+get_home: This is the function that runs when someone visits the home page. It uses a template to create a webpage that shows all the photos.

response_class=JSONResponse: Indicates the server will respond with data in JSON format, confirming the photo was added.

<!DOCTYPE html>

+<html lang="en">

+<head>

+ <meta charset="UTF-8">

+ <title>Photogallery</title>

+ <link rel="stylesheet" href="/public/css/main.css">

+ <link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.googleapis.com">

+ <link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.gstatic.com" crossorigin>

+ <link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Protest+Revolution&family=Protest+Riot&family=Sedan:ital@0;1&display=swap" rel="stylesheet">

+ <script src="/public/js/main.js"></script>

+</head>

+

+<body>

+ <div class="container">

+ <div id="createImage">

+ <h2>Create a New Image</h2>

+ <form id="createForm">

+ <input type="text" id="createImgTitle" placeholder="Title">

+ <textarea id="createImgDescription" placeholder="Description" rows="4" cols="20"></textarea>

+ <input type="text" id="createImgSrc" placeholder="Image Source URL">

+ <input type="submit" class="submit" value="Create Image">

+ </form>

+ </div>

+

+ <div id="imagesList">

+ {% for img_id, img_data in images.items() %}

+ <div class="imageForm">

+ <figure data-img-id="{{ img_id }}">

+ <div class="pin"></div>

+ <img src="{{ img_data.src }}" alt="{{ img_data.title }}">

+ <figcaption>

+ <p>{{ img_data.title }}</p>

+ <p>{{ img_data.description }}</p>

+ <div class="buttons">

+ <button type="button" class="modifyBtn">Modify</button>

+ <button type="button" class="deleteBtn">Delete</button>

+ </div>

+ </figcaption>

+ </figure>

+ </div>

+ {% endfor %}

+ </div>

+ </div>

+</body>

+</html>

+<!DOCTYPE html>

+<html lang="en">

+<head>

+ <meta charset="UTF-8">

+ <title>Photogallery</title>

+

+ <link rel="stylesheet" href="/public/css/main.css">

+ <link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.googleapis.com">

+ <link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.gstatic.com" crossorigin>

+ <link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Protest+Revolution&family=Protest+Riot&family=Sedan:ital@0;1&display=swap" rel="stylesheet">

+

+ <script src="/public/js/main.js"></script>

+</head>

+<body>

+ <div class="container">

+ <div id="createImage">

+ <h2>Create a New Image</h2>

+ <form id="createForm">

+ <input type="text" id="createImgTitle" placeholder="Title">

+ <textarea id="createImgDescription" placeholder="Description" rows="4" cols="20"></textarea>

+ <input type="text" id="createImgSrc" placeholder="Image Source URL">

+ <input type="submit" class="submit" value="Create Image">

+ </form>

+ </div>

+ <div id="imagesList">

+ {% for img_id, img_data in images.items() %}

+ <div class="imageForm">

+ <figure data-img-id="{{ img_id }}">

+ <div class="pin"></div>

+ <img src="{{ img_data.src }}" alt="{{ img_data.title }}">

+ <figcaption>

+ <p>{{ img_data.title }}</p>

+ <p>{{ img_data.description }}</p>

+ <div class="buttons">

+ <button type="button" class="modifyBtn">Modify</button>

+ <button type="button" class="deleteBtn">Delete</button>

+ </div>

+ </figcaption>

+ </figure>

+ </div>

+ {% endfor %}

+ </div>

+ </div>

+</body>

+</html>

+body {

+ background-image: url('../images/wood-background.jpg');

+ width: 100%;

+ font-family: 'Sedan', sans-serif;

+ margin: 0;

+}

+

+.container {

+ display: flex;

+ flex-direction: row-reverse;

+ justify-content: center;

+

+ margin-top: 12.5%;

+}

+

+#imagesList {

+ display: flex;

+}

+

+/* CARD CONTAINER */

+

+figure {

+ position: relative;

+ width: 200px;

+ height: 200px; /* Adjust the height as needed */

+ box-shadow: 0 4px 8px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.1);

+ animation: sway 5s infinite alternate ease-in-out;

+}

+

+figure img {

+ width: 100%;

+ height: 100%;

+ display: block;

+ border: 5px solid white; /* Polaroid frame */

+}

+

+figcaption {

+ text-align: center;

+ padding: 5px;

+ background-color: white;

+ font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

+ margin-left: 10px;

+}

+

+.pin {

+ position: absolute;

+ width: 20px;

+ height: 20px;

+ background-color: red;

+ margin: 0 50%;

+ border-radius: 50%;

+ animation: none !important;

+ border: 5px solid black;

+ }

+

+.imageForm .buttons {

+ display: flex;

+ justify-content: center;

+ gap: 15px;

+}

+

+

+.buttons > button {

+ padding: 2%;

+}

+

+.buttons > .modifyBtn {

+ background-color: green;

+}

+

+.buttons > .deleteBtn {

+ background-color: red;

+}

+

+@keyframes sway {

+ 0% { transform: rotate(-3deg); }

+ 100% { transform: rotate(3deg); }

+}

+

+/* CREATE CARD */

+

+#createImage {

+ background-color: white;

+ display: flex;

+ flex-direction: column;

+ align-items: center;

+ padding: 0 5%;

+ color: black;

+}

+

+#createImage form {

+ display: flex;

+ flex-direction: column;

+ gap: 15px;

+ align-items: center;

+ width: 50%;

+ padding-bottom: 15%;

+}

+

+#createImgTitle, #createImgDescription, #createImgSrc {

+ padding: 7.5%;

+}

+

+.submit {

+ padding: 10% 25%;

+ border-radius: 15%;

+ background-color: #e2e8f0;

+}

+body {

+ background-image: url('../images/wood-background.jpg');

+ width: 100%;

+ font-family: 'Sedan', sans-serif;

+ margin: 0;

+}

+figure {

+ position: relative;

+ width: 200px;

+ height: 200px;

+ box-shadow: 0 4px 8px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.1);

+ animation: sway 5s infinite alternate ease-in-out;

+}

+This part can be a bit confusing, so we’re going to break it down. Don’t get intimidated, we’ll walk you through each step.

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", function() {

+ document.getElementById('createForm').addEventListener('submit', function(e) {

+ e.preventDefault();

+ const title = document.getElementById('createImgTitle').value;

+ const description = document.getElementById('createImgDescription').value;

+ const src = document.getElementById('createImgSrc').value;

+ server_request('/images', { title, description, src }, 'POST', function(response) {

+ window.location.reload();

+ });

+ });

+

+ document.getElementById('imagesList').addEventListener('click', function(e) {

+ const figure = e.target.closest('figure');

+ if (!figure) return;

+ const imgId = figure.getAttribute('data-img-id');

+

+ if (e.target.classList.contains('modifyBtn')) {

+ const title = prompt("Enter new title:", figure.querySelector("figcaption > p").textContent);

+ const description = prompt("Enter new description:", figure.querySelectorAll("figcaption > p")[1].textContent);

+ const src = prompt("Enter new image source", figure.querySelector("img").src);

+

+ server_request(`/images/${imgId}`, { title, description, src }, 'PUT', function(response) {

+ window.location.reload();

+ });

+ } else if (e.target.classList.contains('deleteBtn')) {

+ server_request(`/images/${imgId}`, {}, 'DELETE', function(response) {

+ window.location.reload();

+ });

+ }

+ });

+});

+

+function server_request(url, data={}, verb='GET', callback) {

+ return fetch(url, {

+ credentials: 'same-origin',

+ method: verb,

+ headers: {'Content-Type': 'application/json'},

+ body: verb !== 'GET' ? JSON.stringify(data) : null,

+ })

+ .then(response => response.json())

+ .then(response => {

+ if(callback) callback(response);

+ })

+ .catch(error => console.error('Error:', error));

+}

+This code above does several things

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", function() {

+ ...

+});

+document.getElementById('createForm').addEventListener('submit', function(e) {

+ e.preventDefault();

+ ...

+});

+const title = document.getElementById('createImgTitle').value;

+const description = document.getElementById('createImgDescription').value;

+const src = document.getElementById('createImgSrc').value;

+server_request('/images', { title, description, src }, 'POST', function(response) {

+ window.location.reload();

+});

+document.getElementById('imagesList').addEventListener('click', function(e) {

+ const figure = e.target.closest('figure');

+ if (!figure) return;

+ ...

+});

+if (e.target.classList.contains('modifyBtn')) {

+ ...

+} else if (e.target.classList.contains('deleteBtn')) {

+ ...

+}

+Oh no, you found an empty section!

Carry on, happy hacking!

This documentation is only for Windows.

If your computer doesn’t have Visual Studio Code, install it and follow these steps. In the installation process of Visual Studio Code, don’t change anything and press next until it is installed.

Once it is installed, it will look like this.

Head over to the Python Website and download the latest version. Once you get this pop up, make sure to check the second box of Add python.exe to PATH

After you’ve installed Python, you have to set your interpreter so that it uses the installed Python. To do so, press CTRL + SHIFT + P inside of your visual studio code and type Python: Select Interpreter and press enter. You should see an option to select the interpreter you just installed. Don’t worry about the other options, you should only see one.

You’ve just finished setting up your environment!

You won’t be able to install any of these dependencies if you do not have your Python set up.

In order to access the framework we’ll be using, you must install the libraries first. To do so, go into your Visual Studio Code and make sure that your interpreter is set as the one you just installed. Press Ctrl + Shift + P and type in Terminal: Create New Terminal. Inside of this terminal, type these two commands separately.

pip install fastapi

+pip install uvicorn

+Once these are installed, you are all set up to start creating your website.

There is an extension on visual studio code that allows you to code in real-time with your team members. In order to do so, follow this tutorial.

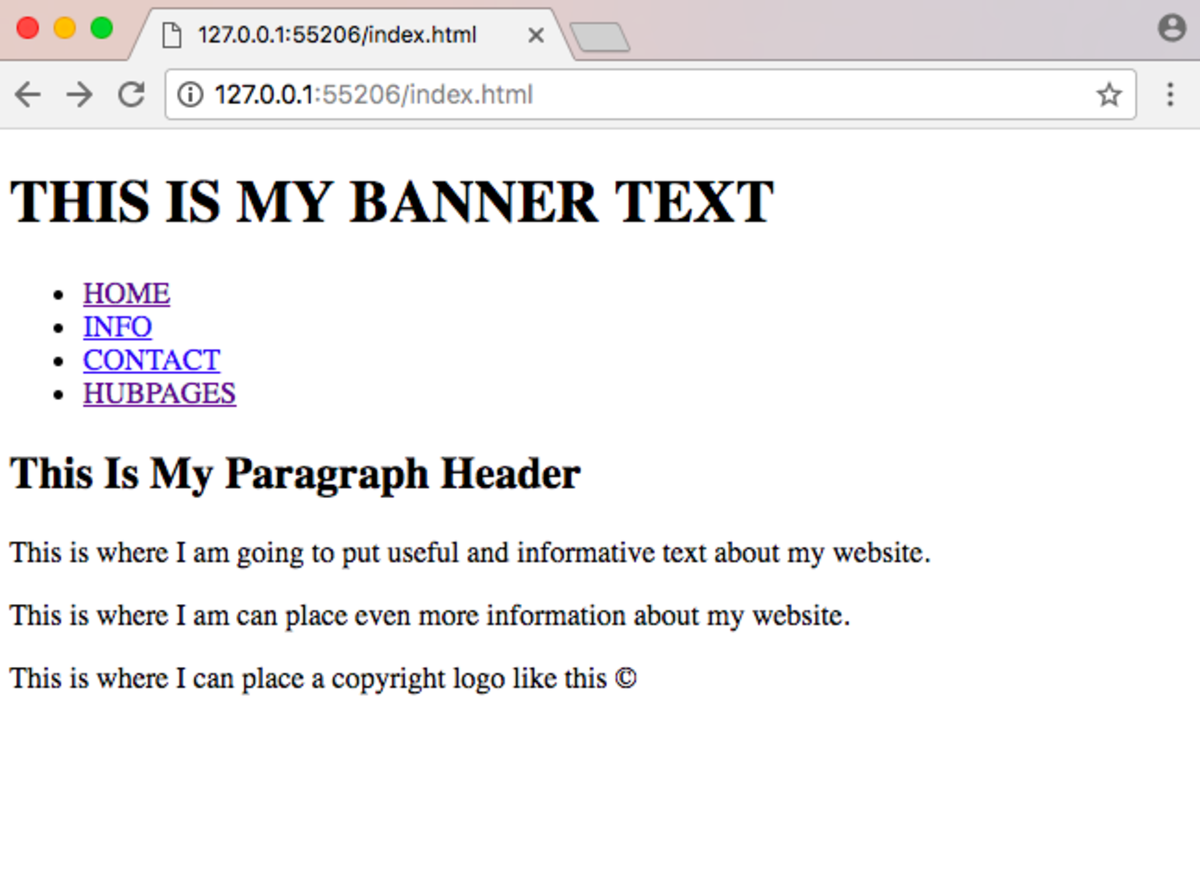

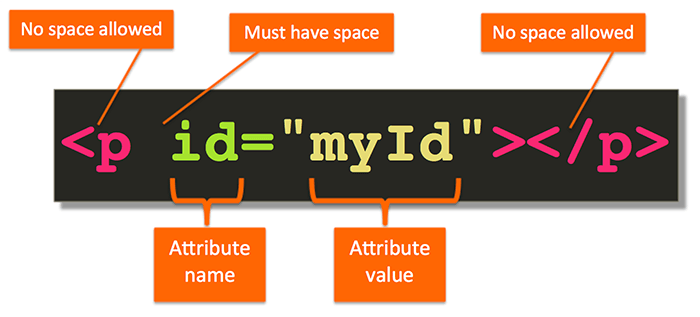

If we imagine the web as a house, HTML lays the foundation and blueprint of the house. Essentially its just text It consists of “tags” enclosed in angle brackets, like <tag>. Tags define structure and content. There are so many different types of tags, from defining lines and headings, links, forms, images and videos down to a simple text as the ones you are reading right now. These tags create a layout of the webpage.

<html>, <head>, and <body>.<h1> to <h6>), paragraphs (<p>), lists (<ul>, <ol>, <li>), links (<a>), images (<img>), and more.<head> tag The head tag represents the set up for our HTML page

The two main components included in every <head> tag are the <title> and <link> tags

We use the <title> tag when we include a title for our webpage

We use the <link> tag for when we want to link a CSS stylesheet to our page, from the example above, we link the “style.css” stylesheet to our HTML page

We will outline the multiple components that every HTML website has:

Header tags represent the titles of our HTML

There are 6 different types of header tags: h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, and h6

To use a header tag, you would do:

<h + "number">(content here)</h + "number"> (where number is from 1 to 6)

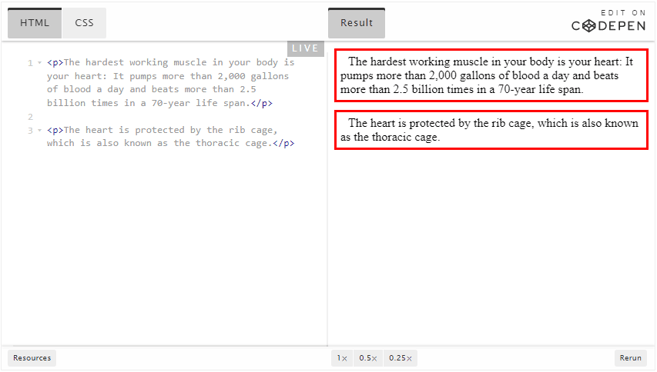

<p> tag The <p> tag is used for big blocks of text, or paragraphs. We use it when we want to include big blocks of text on our website, like for a blog or article

<p>(insert some text here)</p>

<a> tag The <a> tag is a tag is used to link other webpages or websites.

To use an <a> tag, you have to specify the href attribute, which is the url that the tag links to.

<a href="some url">(content here)</a>

In between the opening and closing <a> tags, you insert some text that serves as the link. The default blue color text with the underline shows that the text is a link.

There are two types of lists in HTML:

To specify an unordered lists, you use the <ol> tag.

With ordered lists, your list items would be in a certain order, going from 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth

Same as ordered lists, to add items to your unordered list you use the <li> tag.

To specify an unordered lists, you use the <ul> tag.

Same as ordered lists, to add items to your unordered list you use the <li> tag.

Instead of ordered numbers, there would be a bullet point or some form of separator at the front of each list item

Unordered lists would look like this:

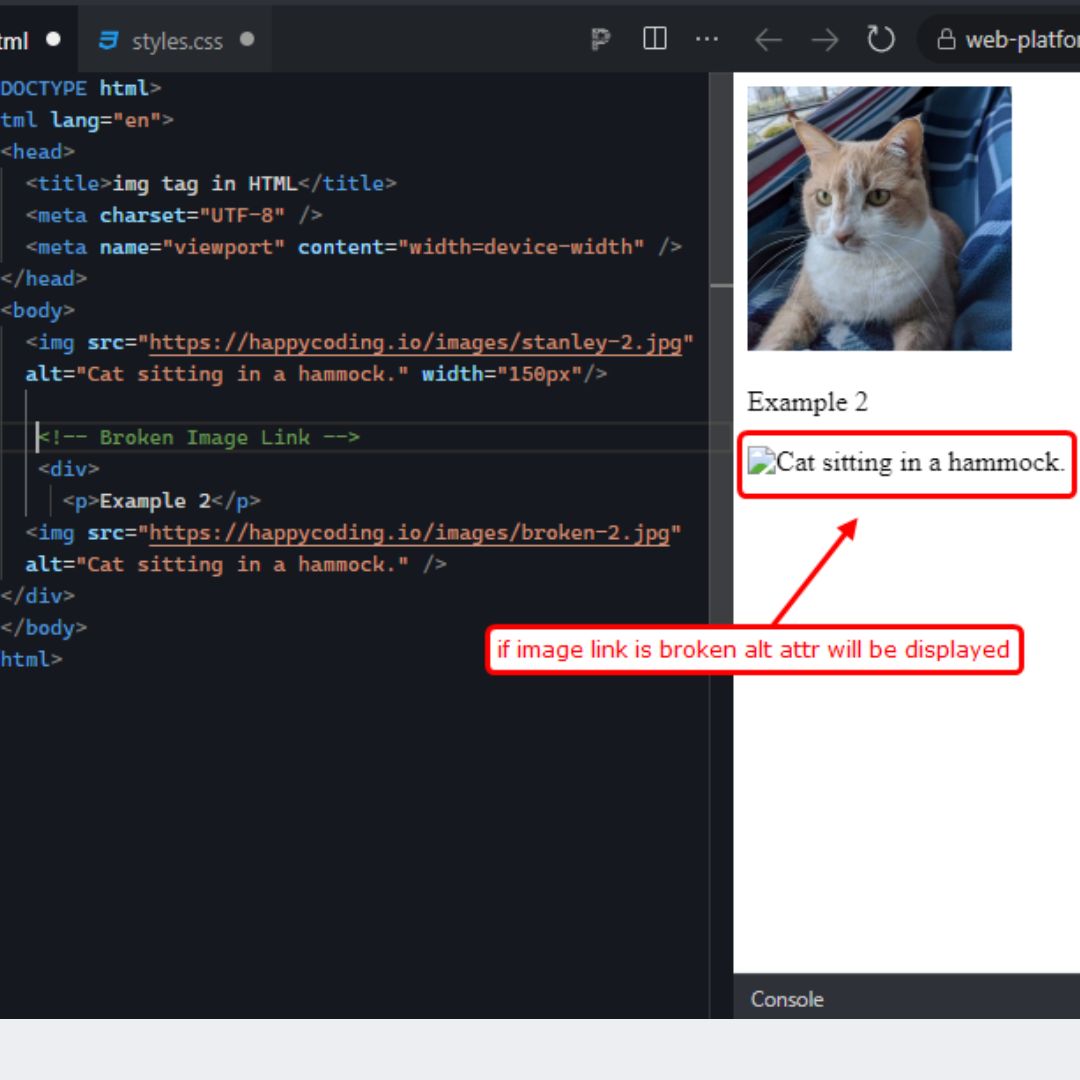

<img> tag The <img> tag is used to add images to our website.

Unlike the other tags, the image tag does not have a self-closing tag, so instead of ending with </img> we just end with />

<img src="image link" alt="describe image here" />

For more HTML tags, visit the link below:

Every house has an architecture style, or a color scheme. All the rooms would follow that scheme according to the what the house should look like. Wouldn’t it be nice to define that in once place? If we have the scheme defined in some place, all the pages we create with HTML would have that style without specifying them repeteadly. This is where CSS comes in. It adds colors, fonts, spacing and styles of the elements used in HTML.

.class), or ID-based (using #id).color, font-size, background, margin, and padding offer control over appearance.When we want to add CSS styling to any of our HTML elements, to select the specific HTML elements we want to style, there are a few different type of CSS selectors we can use

Element selectors are the most basic type of CSS selector. To use an element selector, we just get the tag that we want to apply our CSS to

Say we want to style the tag below

<h1>Hello World!</h1>

To use an element selector, we just get the tag h1 and apply our CSS styles!

h1 {

+ (insert styles here)

+}

+You would use id selectors if you only want to apply CSS styling to one HTML element

To use an id selector, in your HTML, you use the id attribute

<h1 id="any_id">Hello World!</h1>

And in your CSS, you would use the # tag to select the element with a certain id

#any_id {

+ (insert styles here)

+}

+Only one element can have a certain id, you cannot have two elements with the same id

Class selectors allow you to apply the same style attributes to multiple elements

In your HTML, you would assign the class attribute to the tags you want to have the same style

From the below example, we see that there are multiple <p> tags

Say we want to style the first two <p> tags and not the third one. We can assign them the same class, in this case, “paragraph”

<h1>Hello, my name is Deadpool!</h1>

+<p class="paragraph">I am an antihero, I have done good but have also done bad</p>

+<p class="paragraph">I am played by Ryan Reynolds!</p>

+<p>The end!</p>

+To add style attributes to a class, we use the . tag instead

.paragraph {

+ (insert styles here)

+}

+There are many different types of style attributes, but we’ll lay out some basic ones.

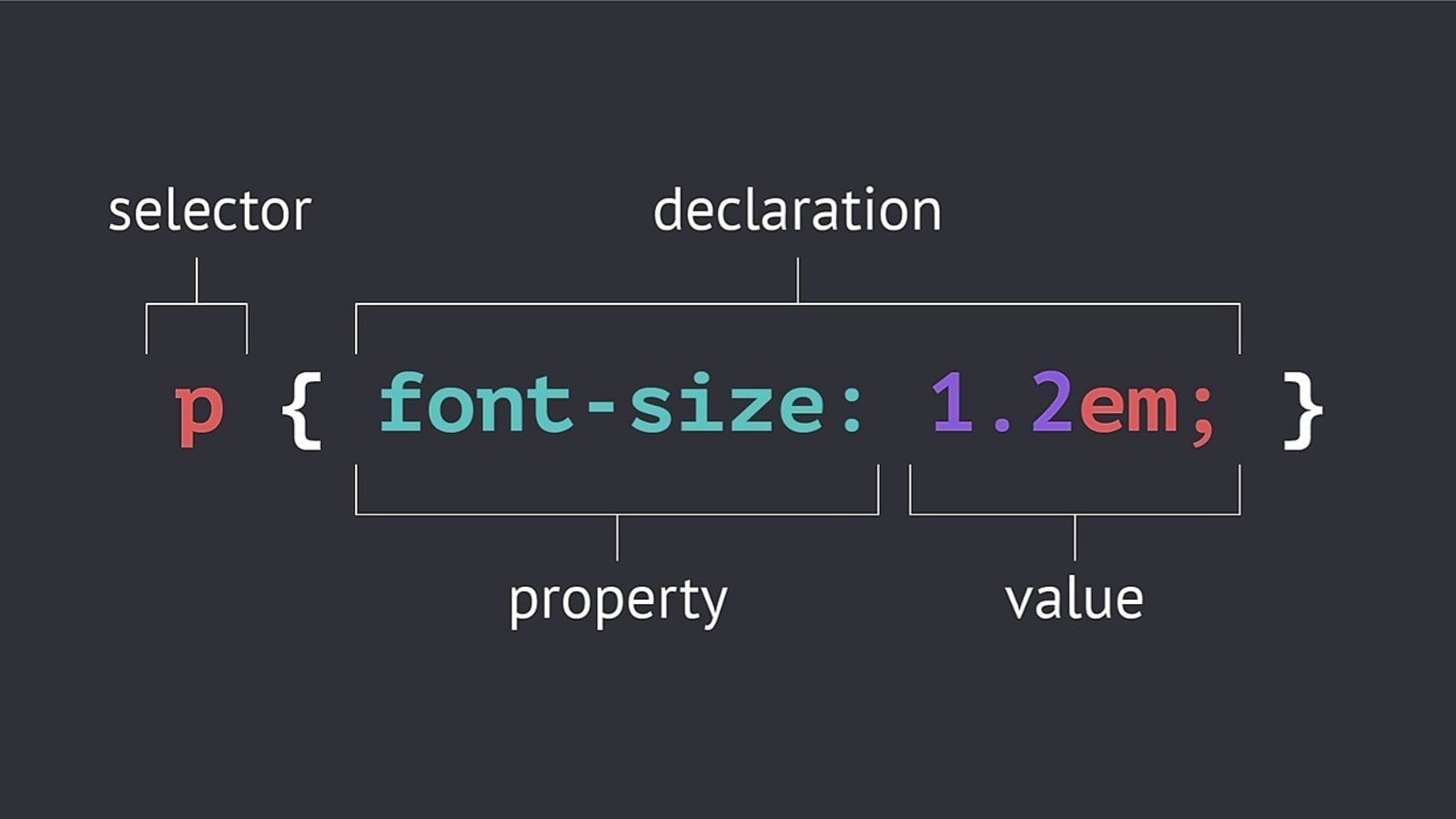

When writing any CSS code, you have to write it like this:

The ones below are style attributes you would use for text

font-size: changes the size of the text (font size is based on pixels, or px)

font-size: 16px;

color: changes the color of the text

color: blue;

font-family: give a specific font to selected text, there are many different font styles out there (the default is sans-serif)

font-family: sans-serif;

text-align: controls how text is aligned on a page, can be aligned left, right, or center

text-align: center;

For a full list of CSS properties, visit the link below:

Now that we’ve created a structure and style, we would want functionality and interaction. If we turn on the switch, what parts of the rooms will light up? Do you want your house to have automatic temperature adjusting to which part of the room you are in? JavaScript is the “code” of the webpage that defines and adds that functionality and behavior. It responds to the inputs and actions user gives, and creates outputs.

if statements and loops.JavaScript allows you to store and manipulate data in variables. It supports several data types including strings, numbers, booleans, objects, and arrays.

var name = "Anthony"; // String

+var age = 30; // Number

+var isDeveloper = true; // Boolean

+| Type | Operators | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic | +, -, *, / | Used to perform basic mathematical operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. |

| Logical | &&, ||, ! | Used to perform logical operations. && is logical AND, || is logical OR, and ! is logical NOT. |

| Comparison | ==, !=, ===, !== | Used to compare two values. == and != check for equality and inequality without type coercion, whereas === and !== check for equality and inequality with type coercion. |

Functions are reusable blocks of code that perform a specific task. They can be called as needed, accept parameters, and return results.

function greet(name) {

+ return "Hello, " + name + "!";

+}

+console.log(greet("Anthony")); // Outputs: Hello, Anthony!

+You can make things happen when buttons are clicked:

<button id="clickMe">Click me!</button>

+<script>

+ document.getElementById('clickMe').addEventListener('click', function() {

+ alert('Thanks for clicking!');

+ });

+</script>

+You can modify the content without needing to reload the page.

document.getElementById('welcome').textContent = 'Welcome to our website!';

+Python is a popular high-level programming language that is used in various fields such as web development, data science, and software engineering. Python is known for its readability, simplicity, and versatility.

In python and like many programming languages, they have print statements. These are what you can use to make the program display an output to the computer screen when you are programming.

Here’s an example of a print statement that displays the words “Hello World”:

print("Hello World")

+When you run the program this is the output:

Hello World

+In python there are these things called comments. Comments are like notes or reminders that we write in our code to help us understand it better.

For example in python we can use a comment like this:

# This is a comment

+Here is another example of a comment being used.

# This code prints the words "Hello World"

+print("Hello World")

+Output:

Hello World

+As we can see comments dont effect the code in any way and they are just there for you as the programmer to see.

Variables in Python are like containers that hold information. Imagine a box with a label on it. You can put different things in the box, and the label helps you remember what’s inside. Similarly, a variable has a name (like the label) and can store different types of information, such as numbers, words, or true/false values.

For example, let’s say we have a variable called ‘age’ to store someone’s age:

age = 15

+Here, ‘age’ is the variable name, and ‘15’ is the value stored in the variable. Later, if the person’s age changes, we can update the variable:

age = 16

+Now, ‘age’ holds the value ‘16’. Variables allow us to store and manipulate data in our programs, making them flexible and powerful.”

We can also use print statements to display the information that is stored in variables. Now lets see an example.

Here we have a variable called “message” that stores the text “Hi how are you?”, and a print statement with the variable “message” inside of it.

message = "Hi how are you?"

+print(message)

+When we run the program this is what gets outputted:

Hi how are you?

+In python data types are essentially different kinds of containers that store different types of information. Just like in real life, where we have different types of containers for storing different things (like a box for toys, a jar for cookies, and a bottle for water), Python has different data types for storing different kinds of information.

You can use these data types for storing different types of data in variables.

Here are some common data types in python:

String (str): Strings are used for storing text, like ‘hello’ or ‘Python is fun!’.

Integer (int): This data type is for storing whole numbers, like 5, 10, or -3.

Float (float): Floats are used for storing decimal numbers, like 3.14 or -0.5.

Boolean (bool): Booleans can only have two values: True or False. They’re often used for making decisions in our programs, like ‘Is it raining? (True/False)’.

List: Lists are used for storing collections of items. For example, a list of numbers [1, 2, 3] or a list of names [‘Alice’, ‘Bob’, ‘Charlie’].

Here are some examples of these different data types.

This is a variable named “message” that contains a String (str) data type.

message = "Hello World"

+This is a variable named number that contains an Integer (int) data type.

number = 10

+This is a variable named “decimal_number” that contains a FLoat (float) data type.

decimal_number = 15.5

+This is a variable named “currently_learning” that contains a Boolean (bool) data type.

currently_learning = True

+This is a list variable named “number_list” that is a list data type that contains a list of Integers. Lists can also contain Strings.

number_list = [1, 2, 3]

+In python we can also store a variable inside of a variable and give them new values.

Here we have the variable age that holds the value of 15. We also have the variable called new_age that holds the value of 16.

age = 15

+new_age = 16

+

+print(age)

+age = new_age

+print(age)

+When the first print statement gets ran, the number 15 gets printed but when the second print statement runs, the number 16 gets printed. This is because when we did age = new_age, we are giving the age variable a new value which is the value of new age.

Output:

15

+16

+In Python there are arithmetic operators that are used to perform basic mathematical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

| Operator | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| + | Addition: adds two operands | x + y |

| - | Subtraction: subtracts two operands | x - y |

| * | Multiplication: multiplies two operands | x * y |

| / | Division: divides the first operand by the second | x / y |

Here are some examples of how to use these operators:

print(5 + 5)

+print(5 - 1)

+print(5 * 5)

+print(10 / 2)

+When we run the program all of these print statements get called and the answers to these mathematical operations get printed (outputted).

10

+4

+25

+5.0

+We can also use variables that hold values to perform these mathematical operations.

number_five = 5

+number_two = 2

+number_one = 1

+number_ten = 10

+

+print(number_five + number_five)

+print(number_five - number_one)

+print(number_five * number_five)

+print(number_ten / number_two)

+Here is the output:

10

+4

+25

+5.0

+Aditionally we can use expressions which are like sentences in math that help us do calculations and solve problems. Here are some examples.

x = 20

+y = 10

+

+add = x + y

+subtract = x - y

+multiply = x * y

+divide = x / y

+

+print(add)

+print(sub)

+print(pro)

+print(div)

+Here is what the output of this code would look like:

30

+10

+200

+2

+In Python we can also add Strings together. This is called concatenation. Concatenation in Python is like combining pieces of text or data together to create a single, larger piece. It’s like putting together pieces of a puzzle to make a bigger picture, or joining words to form a sentence.

Here is an example:

word_1 = "Hello"

+word_2 = "World"

+print(word1 + " " + word2)

+Output:

Hello World

+Concatenation is not limited to strings. We can also concatenate things like lists. For example:

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

+list2 = [4, 5, 6]

+combined_list = list1 + list2

+print(combined_list)

+Output:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

+In Python Comparison operators compare values. It either returns True or False according to the condition.

| Operator | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| > | Greater than: True if the left operand is greater than the right | x > y |

| < | Less than: True if the left operand is less than the right | x < y |

| == | Equal to: True if both operands are equal | x == y |

| != | Not equal to: True if operands are not equal | x != y |

| >= | Greater than or equal to: True if the left operand is greater than or equal to the right | x >= y |

| <= | Less than or equal to: True if the left operand is less than or equal to the right | x <= y |

Here are some examples of them being used:

a = 15

+b = 5

+

+print(a > b) # since a is greater than b, the print statement returns True

+

+print(a < b) # since a is less than b, the print statement returns False

+

+print(a == b) # since a is not equal to b, the print statement returns False

+

+print(a != b) # since a is not equal to b, the print statement returns True

+

+print(a >= b) # since a is either greater than or equal to b, the print statement returns True

+

+print(a <= b) # since a is either not less than or equal to b, the print statement returns False

+Here is the output of this code:

True

+False

+False

+True

+True

+False

+

+Logical operators in Python are like tools we use to make decisions in our programs. Just like how you might use the words ‘and’, ‘or’, and ‘not’ to combine ideas or conditions when you’re making a decision in real life, logical operators in Python help us combine conditions and make decisions in our code.

| Operator | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| and | Logical AND: True if both the operands are true | x and y |

| or | Logical OR: True if either of the operands is true | x or y |

| not | Logical NOT: True if the operand is false | not x |

Here are some examples on how to use them.

a = True

+b = False

+print(a and b) # returns False because b is False. If they were both True then it would return True.

+

+print(a or b) # returns True because at least one of them is True which in this case is a.

+

+print(not a) # returns False because a is True.

+

+print(not b) # returns True because b is False.

+

+Output:

False

+True

+False

+True

+Identity operators in Python are like tools we use to check if two things are the same or different. Just like how you might compare two things in real life to see if they are identical or not.

| Operator | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| is | True if the operands are identical | x is y |

| is not | True if the operands are not identical | x is not y |

Here are some examples for how we can use them.

a = 10

+b = 20

+

+print(a is b) # returns False because this is checking if a and b are the same but they are not.

+

+print(a is not b) # returns True because this is checking if a is not equal to b which is True.

+Output:

False

+True

+Membership operators in Python are like tools we use to check if something is part of a group or sequence. It’s like looking for a specific item in a collection, such as finding a book in a library or checking if your name is on a list.

| Operator | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| in | True if value is found in the sequence | x in y |

| not in | True if value is not found in the sequence | x not in y |

Here are some examples:

In this example we have a list of numbers and we are printing True if 6 is in the list and False if it is not.

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

+print(6 in numbers)

+Output:

False

+Since 6 was not in the list, this statement prints False.

In this next example we have a list of numbers and we are printing True if 9 is not in the list and True if it is.

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

+print(9 not in numbers)

+Output:

True

+Since 9 was not in the list, this statement prints True.

Aditionally we can also use this for Strings.

sentence = "hello how are you"

+print("how" in sentence)

+Output:

True

+This prints True because the text “how” is found inside of the text “hello how are you”.

If statements in Python are like decision-making tools that help our programs make choices based on certain conditions. It is used to decide whether certain code will be executed or not.

Here is an example of the format of using an if statement.

if condition:

+ # code to execute if the condition is true

+Here is an example of an if statement with code to check if a number is positive.

number = 5

+if number > 0:

+ print("The number " + str(number) + " is positive)

+Output:

The number 5 is positive

+What happend was that since the number 5 was greater than zero, it printed “The number 5 is positive” and if it wasnt then nothing would be printed since the condition would be false in that situation. We also used type conversion str(number) because we cannot add an integer and a string together so we had to convert the integer of 5 into a string so there wouldn’t be an error.

In Python Else statements are like a backup plan that gets executed when the conditions specified in the if statement are not met.

For example lets say that we have this code that checks if a person is an adult.

age = 19

+

+if age >= 18:

+ print("Your age is 18 or greater so you are an adult")

+Output

Your age 18 or greater so you are an adult

+This code works but it is not really useful because if the user is under 18 then nothing will happen and there will be no output.

Here is how we can fix this with else statements:

age = 16

+

+if age >= 18:

+ print("Your age is 18 or greater so you are an adult")

+else:

+ print("Your age is under 18 so you are not an adult")

+Output

Your age is under 18 so you are not an adult

+In Python there are also else if or elif statements that act similar to else statements but you use them when you want to check another condition.

Here is an example of using elif statements to see what type of grade you have:

grade = 87

+

+if grade >= 90:

+ print("You have an A")

+

+elif grade >= 80:

+ print("You have a B")

+

+elif grade >= 70:

+ print("You have a C")

+

+else:

+ print("You have an F")

+Output

You have a B

+In Python lists are a data structure that we use to store multiple items is a singular variable. They can also contain elements of different data types. Lists can easily be modiefied and its data can easily be accessed.

Here is how you can create a list with 5 integer elements ranging from 1 to 5:

my_list = [1,2,3,4,5]

+Here is an example of a list of strings:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+Accessing Elements

In programming languages they use what’s called zero indexing where essentially the first index of a data structure like lists or strings starts at zero.

So in this example to access the first element of the list we would do this:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+print(my_list[0])

+Output:

apple

+Modifying Elements

Here’s how we can modify the list:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+my_list[1] = "pear"

+print(my_list)

+Output:

apple, pear, banana

+Adding Elements

For adding elements to the list we can use a list method which is a built in method that we csan use on lists. To add elements we can use the .append() method.

Here’s an example:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+my_list.append("cherry")

+print(my_list)

+Output:

apple, orange, banana, cherry

+Removing Elements

For removing elements we can use the .remove() method.

Example:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+my_list.remove(2)

+print(my_list)

+Output:

apple, orange

+List Length

We can access the length of a list by using the len method which looks like this len(). The len method can also be used for other data structures and types like strings.

Here is how we can use it with iterating over a list:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+

+print(len(my_list))

+Output:

3

+We can use loops for when we want to execute code repeatedly until a specific condition is met. In Python there are two main loops which are the for and while loops. The while loop is used when you want to ececute code until a specific condition is true and the for loop is when you know how many times you want the code to execute.

For loop

We can use for loops to iterate over a list or a range of numbers.

Here is an example of using a for loop for iterating over a list:

my_list = ["apple", "orange", "banana"]

+

+for item in my_list:

+ print(my_list[item])

+Output:

apple

+orange

+banana

+This is how we would use it with a range of numbers:

for x in range(5)

+ print(x)

+Output:

0

+1

+2

+3

+4

+While Loop

We use while loops when we want to execute code until a condition is met then once the condition is met then the loop stops.

For example her is how we can print numbers from 1 to 5:

number = 0

+while number < 5:

+ number +=1

+ print(number)

+Output:

1

+2

+3

+4

+5

+In Python we can use funnctions which is a block of organized, reusable code that performs a specific task. Functions provide a way to modularize your code, making it easier to read, write, and maintain. In Python, you define a function using the def keyword followed by the function name, parentheses ( ) containing optional parameters, and a colon :. The body of the function is indented and contains the code to be executed when the function is called.

Here’s an example of a function that takes a users name and prints it with hello:

def greeting(name):

+ print("Hello " + name + "!")

+

+greeting("programmer") # This is how you call the function (use it)

+Output:

Hello programmer!

+Functions can also return values using a return statement.

Here is an example of a function that adds two numbers togther and returns it:

def add(x, y):

+ return x + y

+

+# Call the function and store the result in a variable

+result = add(3, 5)

+print(result)

+Output:

8

+The starter kit goes over the surface level of web development. It is a very high-level perspective and there’s so much more going on under the cover. Take each explanation with a grain of salt as it’s meant to introduce you to these ideas.

The Internet is like a huge worldwide network that connects millions of devices together. It’s a bit like a massive library, but instead of books, it stores information, pictures, videos, and much more. You can think of it as a place where people from all over the world can share and access information.

Websites are like individual rooms or spaces in this big library. Each website has its own unique address, just like a house has an address in a city. When you visit a website, you’re exploring what’s inside that particular room of the internet library. Websites can be about anything – from sharing news and stories, selling products, teaching things, or simply entertaining people.

Now, web development is the fascinating process of building these websites. It’s like being an architect, designer, and storyteller all at once. People who work on web development use special computer languages and tools to create and design these online spaces.

Making a website usually consists of several teams, kind of how architects, engineers, and workers come together to build a house. When we create cool websites, there are three main groups involved:

Let’s check out what they do!

The design team are like the architects who draw the creative blueprints for the house. They focus on how the house will look and feel, deciding on the colors, layout, and style. Similarly, in web development, the design team plans how the website will appear to visitors. They choose the colors, shapes, and where things like buttons and pictures will go, making the website look fantastic!

The frontend team is similar to the construction workers who build the visible parts of the house that people see and interact with—like the walls, doors, and windows. In web development, the frontend team uses special programming languages like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to create what you see on a website. They make sure the website looks great on your computer or phone, just like how builders make sure the house looks amazing from the outside.

Now, the backend team are like the engineers and the house’s hidden systems—things you might not see, like the electricity and plumbing. In web development, the backend team works on the website’s power system, the databases, and other technical stuff. They make sure everything works smoothly behind the scenes, so when you click a button, the right information shows up, just like when you turn on a light switch, the light comes on without you seeing all the wiring.

You’re familiar with the Frontend, which represents what the house looks like – color, walls, and the structure of the house. Now, let’s explore the Backend, which is what makes the house run and function.

Imagine servers as your house’s brain. They make everything in your house work, like turning on lights, keeping the rooms cool, and making sure stuff runs smoothly. When you want a light on, the brain (server) sends power to the light so it shines.

Databases are like different energy companies delivering specific resources to your house. Each company supplies something different, just as databases hold various kinds of organized information. For example, one energy company might provide electricity, another gas, and another water. Similarly, different databases supply specific data types, keeping things organized like resources from different companies.

RESTful is the method we use to interact with the servers. Similar to how you might switch on lights, turn on the faucet for water, or adjust the thermostat to get hot water or change room temperature, RESTful is a way to allows us to access and receive things from the household system.

Databases are essential for managing and organizing data in a way that makes it easy to access, manage, and update 🔄. Think about the restaurant analogy 🍽. Before you can enjoy a meal, the kitchen needs all sorts of things like ingredients 🥦, spices 🌶, and cooking tools 🍳. A database holds all the bits and pieces of data 📊 that a computer program needs to work, all organized so it’s easy to find and use, just like how a kitchen organizes everything to cook your food. In our web development case 🌐, a database may store data such as user-specific information 👤.

There are several kinds of database, but the only two you need to understand for a introductory to databases are relational and non-relational databases.

Relational databases store data in tables, sort of like grids 📈. Each table is for a different category of information. For example, one table for customer info 🧑💼 and another for orders 📝. These tables can link to each other through shared information, like if a customer places an order, there’s a way to see that in both the customer and order tables.

They’re great when your data is structured and consistent 🏛. This means you know exactly what information you need to store ahead of time, like names, addresses, or product orders. They’re used a lot in systems that need to keep track of things precisely, such as bank transactions 💰 or school records 🏫.

Imagine a well-organized binder with different sections for each subject in school 📚. Each section has pages that follow the same format, making it easy to find and understand information. If you need to see how your math grades relate to your overall GPA, you can easily flip through the binder to find and connect that information 🔍.

Non-relational databases, or NoSQL databases, are more flexible in how they store data. They can handle a mix of structured and unstructured data, like text 📝, social media posts 💬, or even videos 🎥. They don’t require a fixed table structure and can easily scale to handle huge amounts of data 📈.

These are great for big data applications or services that collect a lot of user-generated content, like social media platforms 📱 or e-commerce sites with customer reviews 🛒. They can quickly adapt to changes in the type of data being stored and can handle massive amounts of data 🌐.

Think of a big, expandable folder 📂 that you can throw all sorts of notes into, whether they’re written neatly on lined paper 📄 or quickly jotted on napkins 🍽. You don’t have to organize every piece of information in the same way, and you can keep adding more notes without worrying about running out of space or messing up the order 🔄.

Before we go into what RESTful APIs are, it’s important that we understand that they are just a way for computer sand programs to communicate with one another over the internet. It’s very much similar to how HTTP allows browsers and servers to exchange information. 🌐🖥️

Imagine you’re at a restaurant, a familiar setting we’ve discussed before. This time, let’s focus on how you interact with the restaurant’s ordering system, which can help us understand how RESTful APIs work. 📝

REST stands for Representational State Transfer. It’s a set of rules that developers follow when they create APIs for web applications. Think of it like the restaurant’s menu and the way you order your food. 📋🍲

RESTful APIs operate under a few key principles, similar to how a restaurant functions efficiently:

Understanding RESTful APIs is like understanding how to efficiently place an order and get exactly what you want at a restaurant. It ensures a smooth, predictable process for both the client (you) and the server (the kitchen), resulting in a satisfying meal—or in the case of web development, the data you need. 🎉👨💻

Before we can dive into what a server technically is, we need to understand how computers communicate with each other. Humans communicate with languages, but computers communicate with each other using what we call the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) 📡.

HTTP is the foundational protocol used by the internet. It defines the rules and standards for transmitting and receiving data over the internet 🌍. Imagine it as the common language that computers use to talk to one another. When you want to visit a webpage, your computer sends an HTTP request to the server where that page lives, asking for the page to be sent to you 📤. The server, understanding your request through HTTP, responds by sending the webpage back to your computer in the form of different files which your browser renders for you 📥.

When you enter a restaurant 🍽️, imagine it’s like typing a website address into your browser. In this scenario, you (the customer) are like the browser, or the client, stepping into the restaurant to have a meal. This process is similar to using HTTP on the internet, which is the method your browser uses to communicate your request in a language that the website’s server (think of it as the kitchen where your meal is prepared 🍳) can understand.

Once the website’s server receives your letter 📨, it sends back a package containing everything you need to visit the website, such as text, images, and videos. This package is also sent via HTTP, ensuring that your browser can understand and display the website correctly for you 🖥️.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into what a server is on the internet, drawing from our restaurant analogy. In a restaurant, your server plays a crucial role: guiding you to your seat, taking your meal order, and delivering your food to you. But remember, they don’t cook the food; that’s the chef’s job 🧑🍳.

However, in the digital “restaurants” that are the internet, servers operate a bit differently. Imagine you’re craving to view a specific webpage, much like how you’d order a dish at a restaurant 📜. When you type a website’s address into your browser, it’s similar to placing your order. This is where the web server steps in, acting not just as your server but also as the chef 🚀.

A web server is essentially a computer program that’s ready to fulfill your order. But instead of heading to the kitchen, it searches its digital shelves for the webpage you’ve requested. Once found, it prepares this “digital dish” by gathering all the necessary files — text, images, videos — and sends them directly to your screen 📲.

What sets a web server apart from a restaurant server is its ability to do it all: taking your request, preparing your order, and delivering it to you, all by itself. In this digital dining experience, the server is the multitasking maestro, ensuring you get exactly what you asked for, straight to your device. This makes the web server an all-in-one package — both the server and chef of the internet world, ready to cater to your digital cravings 🌐.

Imagine a house that’s basically impossible to live in. The kitchen is on the 2nd floor, bathrooms are on the first floor, and the bedrooms are tucked away in the basement – a total mess! Living there would be a real headache. Imagine having to climb up to the first floor every time you need the restroom, just because your room is in the basement. Plus, all the cooking happens on the 2nd floor. It’s like a daily obstacle course! 😅

In the web world, bad design is a bit like this crazy house layout – it makes things awkward and inconvenient for everyone. Therefore, the goal of design is to make our home as easy to use and navigate, accessible for everyone, and make it as attractive as possible. 🏠✨

So when creating our website, we have to consider two main things:

Let’s find out what they mean!

Think of UX as the interior design of your house. It’s about creating a space where everyone feels comfortable and can easily find what they need. In web development, UX is all about putting things on a website in a way that makes it easy and fun to use. It’s like setting up a cool online space, arranging stuff so that using the website feels smooth and enjoyable, just like moving around in a well-designed house.

UI is all about making the buttons and cool stuff on the website. It’s like creating easy-to-click, good-looking controls, similar to designing a game controller. In web development, UI ensures the website is not just functional but also visually appealing and easy to navigate.

UX makes the website feel great, and UI makes it look awesome and easy to play around with. 🖱️💻✨

Imagine you’re at a huge amusement park with friends, but you notice that not everyone can get on the rides. Some of your friends are in wheelchairs 🦽, some can’t see well 👓, and others find the loud noises really overwhelming 🙉. It wouldn’t be fair if only a few of you could enjoy the park while others couldn’t, right? This is where the idea of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) comes into play, but instead of amusement parks, we’re talking about technology and software—like the apps on your phone or websites you visit 📱💻.

Let’s think about video games as an example. Imagine you have a friend who loves video games but can’t play them because they’re hard to see or hear, or because the controls aren’t easy for them to use. That’s not fair, right? Everyone should have the chance to play and enjoy the game 🎮.

In the world of technology, not everyone fits the “average” mold. Some people might have difficulty seeing or hearing, others might have trouble moving their hands or arms, and there are countless other differences. When apps or websites are made only with the “average” person in mind, it leaves out a lot of people who could be enjoying them too.

Making technology accessible isn’t just the right thing to do—it also makes sense from a business perspective. When more people can use an app or a website, it means more happy users and customers 📈.

Think about it this way: if you’re making lemonade to sell at a stand, wouldn’t you want as many people as possible to be able to enjoy it? If some friends couldn’t drink it because the cup was too hard for them to hold, you’d want to find a cup that everyone could hold, right? That’s what DEI in technology is all about—making sure everyone can enjoy what’s being created 🍋🥤.

So, next time you use your favorite app or play a game, think about how it was made and whether everyone can enjoy it as much as you do. And remember, in a world where everyone feels included, everyone wins! 🏆🌍

Now that we know how to create good interactions, let’s focus on user experience.

This law suggests that designs which are aesthetically pleasing are perceived as easier to use by people. It’s not just about looking good; a well-designed interface can make users more forgiving of minor usability issues. This effect shows the power of first impressions and the importance of visual appeal in user interface design.

This principle focuses on the time required to move to and select a target, such as a button on a screen. The law states that the time is dependent on the distance to the target and its size. Larger targets closer to the user are faster to select, influencing how designers place important buttons and options in an interface to make them easily accessible.

This law highlights the relationship between the number and complexity of choices available and the time it takes for a person to make a decision. As the number of options increases, so does the decision time. This is particularly important in designing menus, settings, and navigation to avoid overwhelming users with too many choices at once.

This law states that users’ expectations are shaped by their experiences with other websites and applications. If a website functions in a similar manner to others that the user is familiar with, the learning curve is reduced, and the user is more likely to have a positive experience. This underscores the importance of adhering to common design conventions and standards.

According to this principle, objects that are close to each other are perceived as more related than objects that are spaced further apart. Designers use this law to group related information and controls, helping users intuitively understand how different parts of the interface are connected.

This psychological principle suggests that the average person can keep only about 7 (plus or minus 2) items in their short-term memory. This has implications for design, indicating that interfaces should be simple and not overload users with too much information at once.

Also known as the 80/20 rule, this principle posits that 80% of effects come from 20% of the causes. In UX, this might mean that a small number of features are responsible for the majority of a product’s usefulness or that a small portion of users generate most of the traffic.

This rule suggests that people judge an experience not by the overall journey but by how they felt at its most intense point (the peak) and at its end. This is crucial for designing experiences that leave a lasting positive impression, even if not every moment was perfect.

With DEI in mind, let’s explore some principles that can help us be more inclusive.

Ensuring content is readable for all, including those with visual impairments, is key to digital accessibility. Adjustable text sizes and fonts allow users to tailor their reading experiences for visual comfort, making digital spaces welcoming to everyone.

Proper color contrast and sound cues significantly improve usability for users with vision or hearing differences. This ensures that information is accessible and interaction is seamless for everyone.

Alternative text for images is vital for users relying on screen readers, allowing them to comprehend visual content they cannot see, thereby making websites and apps more inclusive.

Voice commands and customizable controls ensure that technology is accessible to individuals with diverse physical abilities, offering ways to interact with devices that suit their needs.

Keyboard-only navigation is crucial for individuals who cannot use a mouse, making digital content navigable and inclusive for users with motor impairments.

Closed captions and transcripts ensure that deaf or hard of hearing users have access to audio and video content, supporting equality in information access.

Providing intuitive feedback on errors helps users correct mistakes easily, improving the user experience and ensuring successful interactions with digital platforms.

User testing with a diverse group provides insights into accessibility and usability challenges, leading to digital products that are genuinely inclusive.

These are the most basic of them all. If you want to explore, you can learn more at Apple’s guideline.

Okay, imagine your favorite LEGO action figure as a cool website or app. The way it looks and feels when you play with it is like the front end. Now, let’s break it down into three main components:

Now, what is each of these components for, and what role does each component play in front end development?

HTML, or Hyper Text Markup Language, acts as the skeleton for your website. Like a blueprint for a LEGO figure, it instructs on assembly and identifies each part. Just as you’d follow instructions to place the head, body, arms, and legs, HTML guides website construction. It ensures everything aligns perfectly to create the desired look and functionality!

CSS, or Cascading Style Sheets, is the paint and accessories for your website. In the case of a LEGO figure, after assembling the figure with HTML, CSS lets you unleash your creativity to make it stand out among the millions of other LEGO figures out there. Picture decking out your LEGO figure in a vibrant superhero costume, a sleek robot shell, or a dazzling princess gown! CSS brings these visions to life on your website. It’s the style guru that adds colors, patterns, and flair to make your creation truly stand out!

JavaScript acts as the superpowers for your LEGO figure. After building it with HTML and giving it style with CSS, JavaScript steps in to add movement and magic. Envision your LEGO figure performing flips, karate kicks, or dancing — it’s all made possible by JavaScript. So, when you click a button and see something awesome happen on a website, like a game starting or a video playing, that’s JavaScript using its magical abilities to breathe life into your creation!

CSS, or Cascading Style Sheets, is like the paint and decorations you use to make your LEGO house look awesome after you’ve built it. While HTML defines the structure and content of your web page, CSS controls how your web page looks, like the colors, fonts, sizes, and layout.

CSS works together with HTML to make your web page look fantastic. It’s like adding all the cool paint colors, decorations, and designs to your LEGO house after you’ve built it. You use CSS to tell the browser how you want each part of your web page to look.

For example, you can use CSS to make your headings big and bold, your paragraphs have a specific font, and your buttons stand out with a bright color. HTML tells the browser what content goes where, and CSS tells the browser how to style and present that content, just like how the instructions tell you where to put each LEGO brick and the decorations to make your house look amazing.

Together, HTML and CSS work hand in hand to create beautiful and functional web pages, just like how LEGO bricks and decorations come together to make awesome creations!

There are different types of CSS styling you can implement:

Inline styling is when you add CSS styles inside an HTML tag

To do inline styling, you add the style attribute inside an HTML tag, and then the specific CSS property inside the quotes of the style attribute, only do styling within the <body> tag, and inside the opening tag only (not in the closing tag)

<h1 style="color:red">Hello!</h1>

This is considered the most inefficient form of implementing CSS styles because if we want to implement multiple CSS properties, it can get pretty jumbled and messy!

To utilize internal styling, you add the <style> element inside the <head> section

<!DOCTYPE html>

+<html>

+ <head>

+ <style>

+ body {background-color: powderblue;}

+ h1 {color: blue;}

+ p {color: red;}

+ </style>

+ </head>

+

+ <body>

+

+ <h1>This is a heading</h1>

+ <p>This is a paragraph.</p>

+

+ </body>

+</html>

+This separates the CSS from the HTML code and makes it easier to read when multiple styles are implemented for a specific element. However, we want to keep our HTML and CSS code separate from each other, and the best way is to keep the HTML and CSS code in separate files

For external CSS styling, we use the <link> tag, which we add to the <head> section in our HTML

<link rel="stylesheet" href="(name of css file).css" />

We add the rel attribute and specify it as a “stylesheet” to specify that we want to add CSS code to our HTML, and then the href attribute to link our CSS code to the HTML

Overall, CSS can make our website look pretty and stylish. Like with our LEGO house, we can use CSS to make our website stand out in its own unique way! _______________________

HTML serves as the building blocks for our website. It represents the different pieces for your LEGO figure, the head, arms, body, legs.

Every HTML page ends with “.html”, where each page has the same starting structure. The <head> contains all of the “metadata” which are information related to the website. The actual content goes inside of the <body>tags.

<!doctype html>

+<html lang="en-US">

+ <head>

+ <meta charset="utf-8" />

+ <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width" />

+

+ <title>My page title</title>

+ <link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css" />

+ </head>

+ <body></body> <!--The actual content goes inside the <body> tags-->

+</html>

+Most HTML tags are structured like this:

One important aspect of HTML is the DOM

The DOM, or Document Object Model, is like the instruction manual that tells you how to put all those LEGO bricks together to build your house.

The web browser is like a really smart LEGO builder. When you open a web page, the browser starts reading through that instruction manual, the HTML code.

The DOM is like a map of your web page, showing how all these HTML elements are connected and organized. It’s a way for your web browser to understand the structure of your page so it knows how to display it properly.

It’s like a blueprint of the web page, showing how all the HTML elements are connected and organized, just like how the instruction manual tells the builder how to connect all the LEGO bricks to build the house.

Just like how following the LEGO instruction manual helps you build your house correctly, the DOM helps the web browser render your web page correctly, making sure everything shows up in the right place and looks the way it should.

The browser knows exactly where everything is on the page because it’s already built that LEGO-like map in its memory using the DOM. This helps the browser quickly find and update different parts of the web page without getting confused, just like how a LEGO builder can quickly find and add or remove bricks from the right spots in the house they’re building!

To learn more about HTML, down below are some resources:

JavaScript is a programming language that works hand in hand with HTML and CSS, forming the backbone of most websites you visit. Think of HTML as the basic structure of your LEGO set, CSS as the colors and styles you apply to your LEGO pieces, and JavaScript as the motor that powers your moving LEGO constructions.

To add JavaScript to your website, you would want to use the <script> tag

You could place the <script> tag either in the <head> tag or in the <body> tag. We add it to the body tag for this example.

To add internal JavaScript to your website, you would insert the JS code directly, as shown below:

<!DOCTYPE html>

+<html lang="en-US">

+

+<head>

+ <meta charset="UTF-8">

+ <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

+ <title>Today's Date</title>

+</head>

+

+<body>

+ <script>

+ let d = new Date();

+ document.body.innerHTML = "<h1>Today's date is " + d + "</h1>"

+ </script>

+</body>

+

+</html>

+However, like with our CSS, we would want to keep our JavaScript separate from our HTML, so best practice is to use external JavaScript, or store it in a separate file.

To add external JavaScript to your website, or have it in a separate file you would have:

<script src="myscript.js"></script>

You would create a JavaScript file using the extension .js, and would ideally want to store it in a separate folder from the HTML. The <script> tag would be the last tag in the <body> section, as shown in the example block of code down below

<!DOCTYPE html>

+<html lang="en-US">

+

+<head>

+ <meta charset="UTF-8">

+ <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

+ <title>Today's Date</title>

+</head>

+

+<body>

+ <script src="path/to/my/script.js"></script>

+</body>

+

+</html>

+This will connect our JavaScript to our HTML and CSS, giving us the power to create a fully dynamic website!